Warfare Strategies (And Marketing Ones)!

Many marketers view their businesses as a continuing war between their company or brand and other companies and brands, with market share the territory that has to be fought over and won. I have come across marketers whose only strategic intent is the annihilation of their competitors.

In the context of warfare, Wikipedia outlines “Strategy (as) the organized deployment of resources to achieve specific objectives, something that business and warfare have in common. In the 1980s, business strategists realised that there was a vast knowledge base stretching back thousands of years that they had barely examined. They turned to military strategy for guidance. Military strategy books like The Art of War by Sun Tzu, On War by von Clausewitz, and The Little Red Book by Mao Zedong became business classics.

From Sun Tzu they learned the tactical side of military strategy and specific tactical problockedions. In regard to what business strategists call “first-mover advantage”, Sun Tzu said: “Generally, he who occupies the field of battle first and awaits an enemy is at ease, he who comes later to the scene and rushes into the fight is weary.” From von Clausewitz they learned the dynamic and unpredictable nature of military strategy. Clausewitz felt that in a situation of chaos and confusion, strategy should be based on flexible principles. Strategy comes not from formula or rules of engagement, but from adapting to what he called “friction” (minute by minute events). From Mao Zedong they learned the principles of guerrilla warfare.

The first major proponents of marketing warfare theories were Philip Kotler and J. B. Quinn. In an early deblockedion of business military strategy, Quinn claims that an effective strategy ‘first probes and withdraws to determine opponents’ strengths, forces opponents to stretch their commitments, then concentrates resources, attacks a clear exposure, overwhelms a selected market segment, builds a bridgehead in that market, and then regroups and expands from that base to dominate a wider field.’

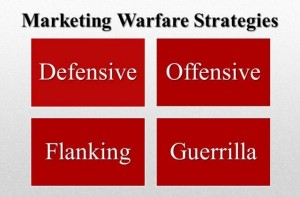

There are many books that have looked at warfare strategies to build into business strategies. My favourite is Marketing Warfare by Al Ries and Jack Trout. The 1986 book borrowed from ideas propounded by von Clausewitz and outlined four strategies that companies and brands should follow:

1. Defensive strategy – Market leaders should follow defensive strategies to guard their position – lessen risk of being attacked, decrease effects of attacks, strengthen position. The key points for the defensive game:

* Only the true market leader should consider playing defense. The market leader has to ensure that the competitors sniping at it are kept at bay.

* The best strategy is the courage to attack yourself. The market leader should never rest on past successes but should constantly look at improving the existing product offering or introducing newer ones. Gillette, for example, plays a great defensive game by launching new products that make its existing ones obsolete.

* Strong competitive moves should always be blocked. Obviously, if competitive moves are not blocked effectively, it will give the competition time and space to entrench itself.

2. Offensive strategy – A strong competitor to the market leader should look at offensive strategies – attack the leader to gain ground. Pepsi has always been a good offensive strategist. The key points for the offensive strategist:

* The challenger’s primary concern should be the strength of the leader’s position. Yes, the offensive player should look at all aspects, including its own strengths and weaknesses, but the primary focus is to understand the key strength of the leader.

* The challenger should look for a weakness in the leader’s strength.

* Attack on as narrow a front as possible. The challenger should not look at a broad attack.

3. Flanking strategy – Players who are no.3 or 4 should be looking at flanking strategies. They should operate in areas of little importance to the main competitors. Marketing high priced, niche products could be a good flanking strategy.

* A good flanking move must be made into an uncontested area. Ideally, a flanker should look at a totally new category that the top two players have not looked at seriously.

* Tactical surprise ought to be an important element in the plan. Surprise is important because it would delay the leader to launch an immediate attack with its immense resources.

* The pursuit is as critical as the attack itself. The follow through to the launch is critical to establish the first mover advantage. Not doing so will play into the hands of the players with bigger resources.

4. Guerrilla strategy – Relevant for small players with little resources – attack, retreat, hide, then do it again, and again, until the competitor moves on to other markets.

* Find a segment of the market small enough to defend. The segment could be geographical, it could be demographic, it could be price.

* No matter how successful you become, never act like the leader. A guerrilla player should always be lean and nimble.

* Be ready to exit at a moment’s notice. If the market takes a downward trend or if the going gets too hot, a guerrilla player should be prepared to exit without incurring heavy losses.

Marketing Warfare is an interesting book and Ries and Trout have given enough examples to amplify the four warfare strategies. They also present an interesting framework within which different players could create a relevant strategy.

However, one must bear in mind that Michael Porter, the guru of strategy, never thought of competition as a form of warfare, a zero-sum battle for dominance in which only the more aggressive prevailed. Porter strongly believes that the key to competitive success is to create unique value; creating value, not beating rivals, should be at the heart of competition.